In this episode, I go over:

The importance of the Red Scare to modern politics

The role of bigotry and antisemitism in the Red Scare

How otherizing contributes to authoritarianism

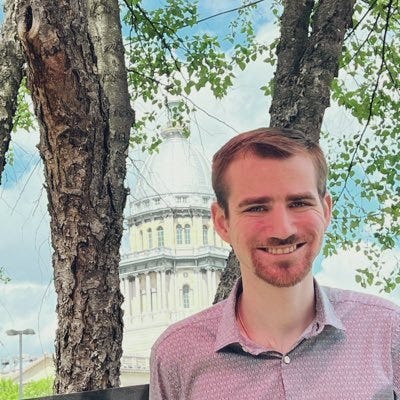

CLAY RISEN is a reporter and editor at The New York Times. He is the author of The Crowded Hour, a New York Times Notable Book of 2019, and a finalist for the Gilder-Lehrman Prize in Military History. He is a member of the Society of American Historians and a fellow at the Perry World House at the University of Pennsylvania. He is also the author of two other acclaimed books on American history, A Nation on Fire and The Bill of the Century, as well as his most recent book on McCarthyism, Red Scare. He lives in Brooklyn, New York, with his wife and two young children.

Transcript

Conor Kelly: Hello, ladies and gentlemen. Welcome to the Progressive American. I'm sitting here with Clay Ryzen, a reporter and editor at the New York Times, the author of The Crowded Hour, a notable book of 2019, and a finalist for the Gilder Lehrman Prize in military history. He also writes about whiskey.

Conor Kelly: However, today we'll be discussing his new book, red Scare Blacklist, McCarthyism, and The Making of Modern America. Thank you for joining me, Mr. Zen.

Clay Risen: Oh, thanks for having me.

Conor Kelly: It's a pleasure. So I think right off the bat, I wanted to start off with, uh, uh, talk about not only how you came to focus on the Red Scare, but what it means for the American people in general today.

Conor Kelly: Sure. Uh, I know you mentioned a lot of Americans aren't particularly familiar with it. In fact, they're not aware, uh, most of the time that they were actually too red scarce. But in particular, what made you wanna focus on the Red Scare and why is it so relevant today?

Clay Risen: Yeah, I mean, I think part of it was exactly that, that there are these.

Clay Risen: Things from the Red Scare that we remember, uh, Joe McCarthy, uh, the Rosenberg trial, the Hollywood 10, and the the blacklist in the entertainment industry. But I think for a lot of people, those things exist separately. And so I wanted to tell a story that really brought them all together because they really did exist in the same, uh, narrative thread.

Clay Risen: Uh, they were all linked together starting in about 1946, going through, uh, for well over another decade. It was this period of intense anti-communist hysteria in the United States. And while there was a lot of reason to be concerned about Soviet espionage and subversion, uh, it was not just blown out proportion, but really weaponized by people who had other agendas, uh, to go after their political enemies.

Clay Risen: And it. Spread far beyond the issues of national security, say at the State Department or in our atomic weapons sector, to include everything from teachers to Hollywood actors to, you know, any, you know, postal workers, any sort of corner of America, regardless of whether it mattered what their beliefs were, uh, the red scare affected them.

Clay Risen: And, and so I wanted to tell that story. I was always really interested in the history. It's, it's sort of coincidental in both. Good, good for me in that you always want buzzer on your book, but bad maybe for the country, and that a lot of these stories now feel like current events. Uh, every day some new story pops up that has a direct reference, uh, back to some episode in the Red Scare.

Clay Risen: It's, it's a, it's quite chilling.

Conor Kelly: And, and to kind of hit off of that, it, it is concerning for a variety of reasons. Uh, not mo not, uh, least of all the role of trauma. I know you've made a point that unfortunately a lot of the histories of the red scare kind of downplay the role of, uh, of trauma. Uh. From World War II and how a lot of people just fundamentally still hadn't fully recovered FU from such a horrible war.

Conor Kelly: And I was wondering what role did World War II play in contributing to the Red Scare? How did it exacerbate, uh, really the security state and its abuses and really just create the environment for this hysteria?

Clay Risen: That's a great question. Uh, there are really two ways I'd say. You know, the first is that. To the extent that the Red Scare was a, a cultural conflict coming out of the 1930s between New Deal progressives and, uh, the backlash to the New Deal and, and anti New Deal, uh, conservatives.

Clay Risen: You know, the war really put kind of a damper on any sort of. Real conflict. So it was only after the war that you saw this conservative backlash really take up the issue of communism in this new context of the Cold War, where it was no longer just this conspiracy theory that communists weren't in control of the government or, or it still was a conspiracy theory, but you couldn't dismiss it.

Clay Risen: Easily. And so people who claimed that communists were living under our bedsheets and in our closets and in the state Department suddenly were taken very seriously. Uh, but the other way the, the war was relevant or, or shaped this, this era. It's exactly as you said that there was a lot of trauma coming out of World War ii.

Clay Risen: We, we remember the post-war era as this period of abundance and good feelings, and, and eventually it was that, but in those first few years, it was marked by, uh, a real sense of insecurity and, and a sense of fear and a sense of, of trauma. There were millions of service members coming back or, or not coming back from the war.

Clay Risen: Those who did had psychological wounds. Physical wounds that were often, uh, is sort of ignored, uh, by the public, which had its own trauma of going through a period of rationing and, uh, and, and sort of states of emergency. There was also a fear that the Great Depression would return and. So in, and then in, in the context of all of that, the red, the Cold War sets in and within, you know, a matter of months after the end of the war, people are being told, oh, actually now we have a new, a new war, a cold War that could be a hot war and this time with nuclear weapons.

Clay Risen: And so everyone needs to be ready for that. And so. Not only were people sort of already fearful, uh, and, and, and insecure about their place in the world and their country's place in the world, but they were also prepared for. These claims about national security, the way that we talked about it during World War II is, uh, is to a large extent set the, the template and set the grounds for the way we talked about it during the Red Scare.

Conor Kelly: Yeah. And, and I've always kind of, I. Wondered about that because, uh, admittedly you're right. I, I think that a lot of the histories don't do enough justice about how traumatic World War II was. Not only because we have a triumphs like view of history that sees us progressing ever onward, but we also are under this.

Conor Kelly: False impression that we can never, uh, fall into, uh, hysteria or, or authoritarian thinking. But to kind of focus on this trauma element, uh, and really kind of transition to huac, I know in the PA in previous interviews you've mentioned that HUAC was not initially, uh, created to hunt communism, but were in, was instead, uh, initially started as a means to root out, uh, Nazi espionage.

Conor Kelly: And I'm curious, how did that transition go from hunting the most extreme of the far right to really. Uh, chasing Boogie, boogeymen and Communists that were under the bedsheets, as you called them.

Clay Risen: Yeah. A lot of it has to do with just the capture of the committee by people who. Fundamentally wanted to use it as a tool to go after the administration.

Clay Risen: Uh, it was created, uh, ostensibly to go after any kind of un-American activities that was its charge, but you're absolutely right that early on the target was, uh, Nazi sympathizers and, and the far right. But because it had a pretty broad mandate, as soon as the chairmanship switched to a conservative Texas Democrat named Martin Dies, who had started off as a pro Roosevelt Pro New Deal Congressman, and then turned rabidly against it, uh, as soon as he got control, the whole focus of the committee.

Clay Risen: Switched and he started going after the administration and he went after labor unions and he even tried to go after Hollywood and a, a lot of it was. Dismissed, uh, you know, by the public, by even other members of Congress. It was seen as the sideshow. He was seen as sort of a joke and as, uh, just an attention grabber, but it did help set the stage for later much more effective, which hunts simply by putting out the idea that Congress had the right to do this sort of thing.

Conor Kelly: Yeah. And by setting a precedent for hunting people, uh, because of their believed political affiliations, you, you can set the standard for future, uh, in, in, in, yeah. Can't speak today, uh, inquisition, so to speak. Uh, but to that point, I, I, when I was going through your book, you mentioned explicitly that many of the, uh, members of huac, uh, or avowed white supremacists and segregationists, and that kind of does.

Conor Kelly: Me to the question of how the New Deal Coalition was starting to fall apart a little bit early on, uh, partially because of racial issues. A lot of people were perfectly willing, as you mentioned, to um, support the New Deal when they thought white people were benefiting. But when black people and other minority groups were, seems that that faded away.

Conor Kelly: How did that kind of manifest and how, how quickly really did that play a role? Or was that there from the very beginning?

Clay Risen: Well, it came out of the 1930s, this tension in the Democratic coalition between the emerging urban northern Democrats who were more liberal, uh, more multiracial, uh, more directly in favor of big government to help out the little guy.

Clay Risen: And what had long been really the dominant sort of the. The cornerstone of the party, the Southern Democrats, and some of them were populous, some of them were in favor of big gov, you know, liked big government projects. Uh, and there's no coincidence that things like the Tennessee Valley Authority and rural electrification and highways, I.

Clay Risen: Directly benefited the south, but they were very wary of the power of this new expanded government to, uh, tilt against segregation. And they were very wary of guys like, uh, Franklin Roosevelt, who was very clearly pushing the party away from segregation, away from the power of the Southern Democrats. And so.

Clay Risen: So huac became a tool in that sort of conflict. Uh, and you're right that early on, especially many of the members were of valid white supremacists. Uh, John Rankin being the most obvious example, he was one of the most powerful members of Congress. And also not just a white supremacist, but a, a, a nasty anti-Semite.

Clay Risen: And now as when Huac was kind of this sort of fringe committee. Uh, no one really paid much attention to who was on it. Once, once the red scare happened and it started to move toward the center of congressional politics, a lot of those. Fringe congressmen or guys like Rankin were pushed aside because suddenly Huac was a, was a hot seat.

Clay Risen: It's where you wanted to be if you were a congressman on the make. And so guys like Richard Nixon came in, who, you know, was himself, uh, not averse to red baiting, but was much more polished, uh, was not a racial bigot, uh, at least didn't. Uh, promote that is his part of his worldview, uh, in Congress. And, and so it, the profile of the committee rose and the, I'd say standard of its members rose, uh, as well.

Conor Kelly: So, and, and it became more legitimate by removing the most extreme members, uh, and the most overt who were saying the quiet part out, quiet parts out loud. It could basically give itself this error of legitimacy. Um, yeah, that's, that's right. Oh, sorry. No, that's, that's absolutely right. And, and, and just to kind of play into that a little bit more, because you mentioned antisemitism and when it comes to the way Helen Bryan was treated, treated by the FBI, you mentioned that they basically tacked on this idea that she was Jewish.

Conor Kelly: Uh. As a way to sort of portray her as inherently dangerous, what role did antisemitism play? Not just in the FBI's uh, examination of Helen Bryan, uh, but also in just how they handled the red scare in general. Since a lot of these, uh, conspiracy theories of infiltration have a lot of antisemitic, uh, uh, underlying.

Conor Kelly: Sure.

Clay Risen: Yeah. So antisemitism certainly runs through both the conflicts of the 1930s, uh, and, and through the story of the Red Scare. Uh, it's not always present, but it often is. I mean, you look at the Rosenberg case and while antisemitism didn't drive every aspect of the case, and I do. Think it's pretty clear that they were, uh, guilty of espionage, the rush to execute them and the public support betrayed a thick context or thick attitude of antisemitism on the part of, you know, the one, these people who had come turn out in watch parties, uh, this is on when they were executed.

Clay Risen: And shout, just really, you know, outwardly. Uh, just, uh, some of the worst antisemitic comments, you know, that, uh, you can think of. And it, uh, it really betrayed kind of one of the motivations underneath this. You know, the idea was that, uh, communism was, um, was often thought of as a Jewish plot or that Jews were, uh, the rank and file of the Communist Party.

Clay Risen: And it's, you know, look, I mean, it's not. Incorrect to say that yes, many communists were, were Jewish, but the idea that it was part of a plot, that there was a communist plot that was, uh, you know, intricately tied with what Antisemites would say, was the, you know, this Jewish plot, uh, controlling the United States from, from the, from the shadows.

Clay Risen: Uh, these things are hard, you know, these were intertwined. Lines of, of conspiracy thinking. And you know, that's not unique to the Red Scare. Uh, it's not unique to the United States, but it shows up very, very clearly. But it's also a little, it's also complicated because many of the, uh, most ardent anti-communist were, were also Jewish.

Clay Risen: Uh, many of them. But not all of them, uh, had been members of the party as, as children, or I mean as, as young people, and for a variety of reasons had turned against the party and become just as, uh, passionately against it as they had been for it and. There was, I mean, there's an entire book, which is, you know, I only touch on briefly, but there's an entire book to be done about, you know, so the role that Judaism and, and Jewish identity played during the Red Scare, because it was both a line, uh, sort of antisemitism was a line of attack, but it was, uh, also in some ways a motivation for people to, uh, get out.

Clay Risen: And, uh, become anti-communist activists, you know, to say, Hey, Jews are not responsible for this. I mean, you found this in many of the most adamant. Uh, anti-Jewish, anti-Communist. They wanted to say, Hey, this, we are, you know, we are, uh, we wanna prove that Jews are good Americans and, and not, uh, not what the anti-Semites say.

Clay Risen: So it's, it's a very complicated story. Um, but I think it's, it's, uh, it's one that I. You can't, you can't avoid when you talk about the subject,

Conor Kelly: and I'll say antisemitism is one of the weirdest prejudices I've had. The displeasure of encountering, yeah. I am not Jewish myself, but there are actually a subsection of people who accused me of being Jewish, uh, because they think I'm part of some of the, some sort of plot.

Conor Kelly: So it is an interesting thing when you brought up Helen, Brian being accused falsely of being Jewish by the FBI, I was like, oh, I've seen that before. Um, but you, yeah,

Clay Risen: and there's, and, and, and look, I mean, there's also, you know, as we know. Always, whether it back then or today. Um, but especially back then, there's also just a, a casual antisemitism, right?

Clay Risen: Mm-hmm. Uh, where people just draw certain assumptions about, and the true with anti-black racism or, or any kind of prejudice, you know, sometimes we think it's always explicit and passionate and angry and, um. It's not always that. Sometimes it's just something that sits in the back of someone's mind and guides their assumptions about other people.

Clay Risen: Uh, and, and that's dangerous as well. And I think that's what, what you saw with Helen Bryant. There was just this assumption. Well, you know, uh, she works for civil rights. She, uh, you know, is active in peace projects. Uh, she, I don't know, to the person writing the report kind looks Jewish, so we're just gonna say she's probably Jewish.

Clay Risen: Uh, why that's even relevant. Don't know. But that was, that was a part of, and it, and it spoke volumes that someone took that as a note.

Conor Kelly: Yeah. And, and this is where it's kind of one of those things where you have to balance the, the understanding of this as, uh, as a, just a regular hysteria. And also the fact that it was also a, a serious issue of prejudice.

Conor Kelly: Uh, one of the things when I was in college, I, I was looking into was the role of white citizens councils in portraying, uh, the civil Rights movement as being controlled by Jewish people because there was this. Patronizing attitude of only Jewish people could be this intelligent, to organize these people, these, these, these black people can't advocate for their rights on their own, that kind of nonsense.

Conor Kelly: But to get into, uh, that kind of thing and how, and to turn to, to turn to today, uh, I I was wondering to what role do the, do these kinds of themes of anti-black racism, antisemitism and conspiratorial rhetoric appear in modern right wing circles and even in, in some left-wing circles as well.

Clay Risen: I mean, look, I would be the umpteenth person to comment on the complicated role that antisemitism plays in, in modern politics, uh, in a way that I think for people certainly of my generation, feels a little.

Clay Risen: Strange, uh, because I grew up with a real, um, you know, I think generally in the country, a, a pretty small p progressive idea about American history that we were, you know, never a perfect country, but moving forward, leaving behind prejudices. And while I. Those prejudices still exist. They're nothing like the past.

Clay Risen: So we look back and say, oh, there was a point in time when Jews weren't allowed into a lot of colleges or into, uh, certain, you know, white shoe law firms. But that's not the case anymore. We've moved beyond that and now to see. In the 21st century, those hatreds, reemerge, and again, as you say, on both sides, both the right and the left, in ways that are different, but often the same and, and always with the same sort of set of assumptions underneath it.

Clay Risen: Uh, you know, the same thing with anti-black racism. Uh, it has been. I think it doesn't even take someone of of my age to see this. I think anyone who lived through, uh, or experienced the, the George Floyd protests and watched that might have come out of it and said, Hey, you know, we as a country are really, I.

Clay Risen: Uh, taking a giant step forward in that idea that this is all, this march of progress toward a certain end. And, and now to see in 2025 that a lot of those achievements were temporary. They were maybe not in great faith. They were done not in great faith. You see a lot of companies pulling back on promises that were made in, uh, the immediate aftermath of George George Floyd's murder and, and an attempt to erase a lot of what.

Clay Risen: People on the left have considered achievements and, and kind of a consensus of how to talk about these things. And so it's, it's dispiriting to see that. But I think certain realists would look at this and say, well, I'm not surprised at all because this is just the country reverting to its mean. And that's, uh.

Clay Risen: You know, it's, uh, it's hard not to sympathize with that point of view at, at this point in, in, in the 21st century.

Conor Kelly: And, and I've, I've, I'll admit, I participated in, uh, the, the George Floyd protest. I got really enthused thinking we were gonna turn the, the tables. But now I think one of the things I've started to realize, and a lot of the people have started to realize, is that nothing is inevitable.

Conor Kelly: It can always get worse, and in many cases it does, uh, without people actively pushing for it and putting, uh, institutional power behind it. But to, uh, kind of turn towards how that prejudice has been weaponized in today's society, in particular with the Trumpist movement. I know you didn't, uh, set out to write a book on Trump, but you do mention that there is a, a, a bit of a line between the Red Scare and McCarthy Era politics, uh, with the rise of modern Trumpism.

Conor Kelly: And what would you say would be like just the top, uh, common themes with Trumpist politics and McCarthy era? Uh, redbaiting.

Clay Risen: I think certainly you can point to any number of tactics, uh, that are very common from the McCarthy era, from McCarthy himself and, and today. But I think the real through line is the end of the red scare.

Clay Risen: I. For a lot of Americans felt like just a return to normal, that the fear was gone and that, uh, you know, in their minds the threat had passed. But for a hardcore of Americans, the, the threat I. Had won, essentially, uh, they felt like McCarthy had been fighting a good fight, but that he had been defeated, uh, sacrificed.

Clay Risen: He was a martyr, and we're not talking about a small number of people. When McCarthy died, he had something like 25 to 30% support in the United States, and these were people who truly believed that there was, uh, not just inefficiency or bad policymaking. At the federal, federal level, but an active conspiracy.

Clay Risen: Uh, this cabal of left wing elites, uh, communists, antier, whatever, uh, running things and that, uh. That was the, the long-term fight, right? That the new deal, the modern federal government, the liberal state, had to be demolished. And so even as, you know, sort of centrist or let's say a, you know, mainstream conservatism accepted the broad outline of modern politics and in fact participated in it, or modern policymaking.

Clay Risen: You know, there always was this fringe and it popped up, uh, from time to time. You see it under, uh, Goldwater, uh, and the Goldwater movement, uh, years later, Buchanan and the Buchanan Eye Populist Movement. And, and I think you see it again today. And, and not only is it similar, but there are explicit links, whether you look at intellectual influences or even figures who, uh, mentor and pass down, uh, this set of ideas, institutions even that, uh, either.

Clay Risen: Influence other institutions or, or have kind of a knock on effect. And so I think while that's largely outside the scope of the book, I do think I sort of end with a brief sketch of what that kind of looks like. I think that there's more work to be done on that. There's some wonderful books out there about it.

Clay Risen: But, but I do think that you can see in the rhetoric of many people, uh, on the right today that. Direct through line. And, and in some ways today is we're seeing the achievement of what a lot of people in the 1950s in the red scare could only dream of. The dismantlement of large parts of the modern federal government, uh, and the rooting out of supposed, uh, left-wing radicals.

Clay Risen: Uh, that's, that was the dream. And, and now it's being achieved.

Conor Kelly: Yeah. And, and then you kind of mentioned the dismantling of the, uh, government agencies and I think that kind of leads to what I was gonna get into with Doge. I know mostly the argument for Doge is not necessarily, uh, conspiratorial in the anti-Semitic or anti-black sense, although there is certainly an element of like how they talk about civil rights programs.

Conor Kelly: But when it comes to this fear of this so-called deep state, this idea that there is a group of people in control of the government and it must be dismantled. It seems to me that there is a, an element of, of seeing the government's actions, uh, as inherently illegitimate. And then when people protest against that, uh, that, uh, view of illegitimacy, it reinforces the narrative Similar to how McCarthyite who lost, saw their loss as a means to justify their previous belief.

Conor Kelly: And to me, what can be done to kind of pull people out of that perspective? Because once people get locked in this circular reasoning, it, it, it almost takes on a. A cultish narrative that is extremely dangerous.

Clay Risen: Yeah. Look, I mean, I think describing the reality rather than playing to the, uh, the conspiracy theory, uh, is, is core to that.

Clay Risen: Uh, good information is always, uh, the most important tool now. These days, I think that that's, uh, harder to do than ever. Uh, the mainstream media is not nearly as powerful as it used to be. While there's a lot of, uh, al let's say alternative forms of media that are very partisan, that are spinning a very different story and, you know, to talk about Doge, I mean, I think that's one great example where depending on how it's explained and how, uh, even how people in the government talk about it.

Clay Risen: Sometimes they talk about it as, look, this is just about government efficiency and we're just, uh, we need to, uh, we really just need to go in and, and clean out the waste, which is hard not to agree with. Right. Of course. If, you know, we want our tax dollars spent, well, uh, now other people talk about it or they look at it as, uh, you know, in much more.

Clay Risen: Well, crusading terms or nefarious terms, you know, that, that Doge is fundamentally about dismantling, uh, this, uh, evil federal structure, right? And getting rid of woke policies that have infected, uh, you know, terminally infected the federal government and whatever. I mean, that's, uh, but. Depending on who you are, you may hear one side or the other, or one version or the other.

Clay Risen: And, and I think that's also where you sort of wonder. I mean, I think for the people doing it, it's probably a little bit of both. Um, you know, I don't think everybody in involved in it. Believes in a conspiracy theory, but I think that when you look at Elon Musk, for example, and the way he talks about what his job is, sometimes he says one thing.

Clay Risen: Sometimes he says it's the other. I, I think he probably believes that he's doing both.

Conor Kelly: And, and what I've, I've been kind of mulling over while trying to figure out how to go about, like, talking about this issue with people because I, I do engage a little bit in, uh, political canvassing and, and, and kind of that kind of operation is one, how do you reach people who are not really sure where they're supposed to get their information?

Conor Kelly: And you mentioned, uh. The mainstream media. And one of the things I've written about and raised concerns about is, well, I guess there is a, a partisan media, and I'm running a show called the Progressive American. Uh, there is an element of, of what I do that is in this commentary sphere, but really good commentary and really good public media, or even media like this does depend on that.

Conor Kelly: Mainstream media and private equity firms like Alden Global Capital have really got a lot of local newspapers and, and, and media environments. And so I guess the, the. Question I have is to what extent do the, the, these cuts reinforce moral panics and make it easier for them to spread?

Clay Risen: Yeah, I think that's, I think that's absolutely right.

Clay Risen: And, you know, look, I, while I think there's a huge crisis for local media, uh, especially when it comes to the coverage of local issues, uh, there's really no replacement for good local, locally reported, locally owned. Media. Um, and that's largely disappearing. On the other hand, there are lots of ways to get the news, especially national news, a lot more than there used to be.

Clay Risen: And in some ways that's a good thing. People have access to lots of different angles and lots of different, uh, takes and, and, uh, that in an ideal world means that you'll have better informed readers, uh, or, or news consumers, but. In reality, it takes a lot more work on the part of news consumers. Uh, you have to be willing to go out and, and find those sources.

Clay Risen: And whereas in the past you could simply, you only had a few TV channels to choose from. You only had a couple of newspapers to choose from, and they were all largely cut from the same cloth. And, uh, you know, today there's a lot more opportunity and a lot broader, uh, sort of buffet of options, but you really have to look to find them and be willing to consume different sources.

Clay Risen: Uh, because if you just kind of follow the old model and you say, okay, well I'm just gonna follow Fox or M-S-N-B-C, then you're really only going to get a certain amount of news. Um, and, uh. You know, a certain angle and and a certain perspective, and whereas that might've worked in the past today, I just think you have to be much more active in searching to find some approximation of the truth.

Conor Kelly: Yeah. And, and that's one of the reasons I keep saying it to everybody I like interact with on this question is don't watch the news, read it, unless, of course it's my show, then it's fine.

Clay Risen: No watching. Okay. Watching, listening, reading. Yeah. Everything, whatever. You know, I try to be as, uh, broad in my news consumption as possible.

Clay Risen: Uh. Because I try to be a, a, try to be critical in my points of view, try to see everything with a grain of salt and, and hopefully come to my own conclusion. Uh, I think the worst thing that can happen is that people just sort of let commentators tell them what to think.

Conor Kelly: Yeah. And, and, and this is where like when I say like.

Conor Kelly: Don't watch the news, read it. I, I emphasize this point because it takes a lot of time to fully grasp what's being discussed, what's being expressed. And the other thing is with like online news, especially when it's in, in digital format and you read it, there's a lot of links that people can go and check the source material that is being provided by the people that are doing that writing.

Conor Kelly: And I think that's really important and, and this kind of unfortunate. Perspective that people keep bringing up is don't trust the media. Don't trust the media. The media always lies. And I do think that kind of helps, uh, people like Donald Trump and other, uh, uh, other reactionary forces and really, um, I wouldn't, wouldn't wanna say debauch, uh, irresponsible commentators.

Conor Kelly: Yeah. Being able to spread their propaganda both on the left and the right. Um, but to the other side of this. My concern is that we have a lot of people who seem to still think McCarthy was right, that these, uh, yeah, commun these fears of communist infiltration. This fear of a Marxism being thrown around, irrespective of whether or not they know what that means, still has.

Conor Kelly: The light of day, and I'm wondering where did that come from? Like how did that maintain itself after seeing so many people lose their wellbeing, lose, lose their freedom, their jobs, and really their lives?

Clay Risen: Well, look, I think it comes down to, you know, two really competing ideas about what America. Is about or what it should be.

Clay Risen: And they're, they don't have to be diametrically opposed, but for certain people they are. You know, on the one hand we are a country of, uh, you know, a Christian country, a self, uh, self-reliant country. We ourselves are self-reliant. Frontiersmen, going back to, you know, these sort of myths about. The founding of America and the, and the, the settling of America by, or the takeover America by, by white settlers.

Clay Risen: And, you know, that's, uh, for a lot of people next to the Bible, as you know, they're, they're guiding light. And then there's a whole other point of view that is. You know, America is never perfect. America is, uh, is building on itself and that America is fundamentally a place of diversity and pluralism. And you need a strong government to both check the power of capitalism, uh, and to, you know, ameliorate some of its impacts, but also to, uh, you know, to be there to settle conflicts between different groups of people.

Clay Risen: And over, ever since that second side emerged as a pretty powerful defining force. In the 1930s, there's been a belief on the right that, that it is fundamentally un-American, right? Because it's so violates their view of what America's ideal, you know, what it's supposed to be. And you know, I think for a lot of people it's uh, they take it.

Clay Risen: Realistically, but for a number of people, they take it to the extreme and say, you know, people on the left are, are evil. Uh, people on the left are un-American. Not just, they have a different idea about America than I do, but they are evil. They're doing something evil to America. And, and that becomes a very useful tool in a lot of ways.

Clay Risen: Uh, it becomes very easy to then say, well, anyone who pushes for civil rights, if I'm a southern segregationist, well, that's not an idea that I grew up with. Uh, that's not an idea that I consider, um, you know, at all in sync with my view of America. Therefore, it's. It is un-American, right? And it's very and very powerful way to, to demonize, uh, ideas that sort of tilt against.

Clay Risen: You know, the, the right's conception of America. So, you know, I think that that's, it's kind of why it's always stuck around, right? It's just a very easy, and you see it today in the way that President Trump talks about, uh, the left, right? It's never just liberals, it's never the Democratic party. It's always, you know, the radical Democrats.

Clay Risen: Um. No matter how far to the right, how conservative a Democrat is, he's gonna call them a radical Democrat. Um, and, and because it's a very useful way to say, those people are not American, right? They're not, fundamentally, there's something un-American about them. And, uh, I, I, I think this will probably be with us for a long time, certainly longer than any of the, you know, president Trump or JD Vance or anybody is, is in office.

Clay Risen: I mean, we're always gonna have this conflict.

Conor Kelly: Yeah, once the genie's out of the bottle, it's kind of hard to put it back in. It

Clay Risen: is. It's.

Conor Kelly: And I just, I look at this and it's especially disheartening 'cause I'm 26. Uh, I've pretty much spent most of my political career and even my writing career, uh, and even just like the podcasting career with, with the consequences of one man's decision.

Conor Kelly: And I think that's what makes. Uh, makes, uh, the Trumpist movement a little more distinct from the Red Scare, uh, is that there seems to be this cult of personality Yeah. Around one man, a man who doesn't really embody a lot of the so-called values that they, they hold onto, especially when it comes, I. To, uh, Christianity.

Conor Kelly: Um, but I, I do think that there, we also have to be careful because a lot of voters, uh, in the 2024 election and really in 2020 as well, were mostly pocketbook voters. A lot of Americans are unfortunately, uh, heavily focused on their pocketbooks in the short term, and they don't see the long term picture, but.

Conor Kelly: To some extent. I also think that plays a role in complicity. And I was wondering what role did the complicity of many Americans, uh, contribute to how the Red Scare developed, how it went on for so long and how destructive it was?

Clay Risen: Well, I think one through line that you could draw is that for most Americans, politics is, uh, secondary or tertiary consideration, and it enters into the focus of their.

Clay Risen: Thinking only when it directly affects something that's right there in front of them. Um, not all Americans. Some people are very concerned about politics, uh, on a regular basis, but for most people it's, you know, and, and finances and personal economics. As you say, pocketbook, you know, that's the most common way, right?

Clay Risen: If it's suddenly seems like the economy's going down, um, you, they. People blame the president. It's often this very reductive story as if the president were responsible for inflation or job cuts, and rarely is that really the case. But so I think, you know, that's certainly. An issue now. Uh, I think that's, as you said, you know, a reason why Trump was so successful in his races, but it was also in a different way what I think you'd say about the Red Scare and that a lot of people didn't think a lot about the red scare.

Clay Risen: You know, it was not if you didn't have, if you were not a progressive or a hardcore conservative, it was something that was happening, but it happened to other people. I. And you are aware of it maybe, but not really caring. And what came through to you was a, uh, maybe you believed that there really was a threat out there, and you thought that it was justified to go after communists wherever they were, or the fear came through to you and you got the message that.

Clay Risen: For the time being, at least it's best just to keep your head down and, uh, maybe not speak out, maybe not support people who might oppose the red scare and, you know, so that's, and, and that's why someone like McCarthy was able to rule through terror for so long, because I think it's a combination of people who actively supported him and people who.

Clay Risen: Were afraid of him, and then people who just didn't care. And that's unfortunately a pretty clear through line throughout American history, and I think it's one thing that defines our political landscape today.

Conor Kelly: Yeah. Uh, apathy is one of the most dangerous political belief systems in American history, if I'm being completely honest.

Clay Risen: Yeah. I mean, I think it's a, it's an irony of American success. I mean, we are a. We've been so successful at creating a stable country for so relatively stable for so long, and you know of. A pretty efficient, pretty, you know, contrary to what people think, you know, we have a pretty efficient government and government system.

Clay Risen: One that stays out of people's lives for the most part. And you know, certainly compare it to other countries and other eras. But because of that, we've created a space where people. Can completely ignore politics and they don't have to think about these things. And they don't even have to think about the fact that they don't have to think about it.

Clay Risen: Mm-hmm. And that's great until it's terrible because then you don't have, you know, in a crisis, you don't have an informed, engaged electorate. And that can be, uh, you know, dangerous in all sorts of ways.

Conor Kelly: And, and, and to kind of hit on that note, I, you talked about how they, there is this attitude of like, if, if you weren't directly affected by it, it was easier to ignore.

Conor Kelly: And I, I think that kind of plays a role in the backlash right now that the Trump administration is putting forward towards. The pro-Palestinian protests, um mm-hmm. Mamud, Khalil is a perfect example of that. You can argue whether or not his flyers were acceptable. I would argue that if assuming he was the one who was giving those out, those were definitely, uh, less than ideal to put it very, very lightly.

Conor Kelly: Yeah. But at the same time, he's not as far as I'm aware. Has not been charged with any crime and the ability to otherwise people, because he's not a citizen, but instead has a green card kind of plays on that role of, yeah. Of otherwise removing people who are vulnerable, seeing them as not part of the system, and that they're not entitled to human dignity and human rights.

Conor Kelly: Do you see a, a line between how the, uh, protest movements that occurred, uh, on, on campuses during the Red Scare, uh, were treated and, uh, do you see a line to the, to, to the Palestinian protests today?

Clay Risen: Yeah. Truth be told, there really weren't protests during the Red Scare. I mean, one of the things I think is really noteworthy about that period, uh, versus today is, is the lack of a protest movement.

Clay Risen: Mm. Uh, you know, we, there was in the 1930s, there was, uh, pretty solid, pretty strong through line or, or strain of. Street activism, uh, a lot of it based around labor rights, uh, but also marches in favor of civil rights and women's rights and peace and what have you, uh, after World War ii, that just really wasn't, I.

Clay Risen: Part of the, the conversation, and partly it was just because most Americans just wanted to get on with their lives. Uh, partly it was because, you know, people were afraid. But it also set the stage for the 1960s where you have a new generation of people, the baby boomers coming along and looking at how their parents had responded to a period of.

Clay Risen: Uh, cultural and, and political oppression, uh, and, and coming away with, uh, a very critical perspective. You know, they looked at their parents and said, what, what do you mean you didn't stand up to McCarthy? What do you mean you didn't, you weren't out in the streets. What is wrong with you? And it was part of the, the critique.

Clay Risen: Posed by the new left, which was, you know, the reason why we're here, or why we're, why we're, uh, people are dying for civil rights. Why we're involved in Vietnam is because our parents' generation was complicit in that. And so we are not going to be complicit. We're going to stand up. And, and I think that, you know, setting aside the details of, uh, the excesses or mistakes of the sixties era, I think one of the great things to come out of it is an abiding commitment.

Clay Risen: Not just on the left, but across America, uh, to speak out and, and to express oneself. And so today, you know, I think we see a pretty healthy expression of political descent on campuses and, uh, very much like the sixties, but not at all, like the fifties, late forties and fifties. And that's, that's a good thing.

Conor Kelly: Yeah. And, and I think the thing that a lot of Americans are, unfortunately, and you mentioned this with the apathy side of, of things, a lot of Americans are unfortunately, uh, under the impression that politics is an inherently dirty thing. Mm-hmm. And that, to me is a, is a dangerous idea for two reasons.

Conor Kelly: The first being if you think something's dirty, you're gonna avoid it. So you're never gonna actually try and learn about it. And if you're never gonna learn about it, you're never gonna have your voices heard. So you, it reinforces the first point. And one of the things I really hope that. Interviews like this and really discussions in general about this historical period, uh, point out is that there needs to be more political action.

Conor Kelly: People need to learn more, they need to be able to inform themselves to really, truly consent to their government. But, uh, uh, as, uh, leading into my last question, if there was one core warning, one core point about the red scare that you would want Americans to remember, what would that be?

Clay Risen: I mean, it would be, I think exactly what we're talking about that the.

Clay Risen: Look, my book explains why the red scare happened the way it did, why it happened. When it did it, it puts it in history. But one of the warnings that I try to bake into that is that just because it happened at a particular time in a particular way, uh, doesn't mean that it won't happen again in some other form.

Clay Risen: I mean, we may not call it a red scare, uh, you know, but this idea of. Political hysteria. Justifying political repression is something that can happen again and again in different forms, maybe different enough where people don't even think about the historical precedent. And yet the lessons of the historical precedent are absolutely vital for maintaining, uh, a, you know, strong, strong descent.

Clay Risen: And I say that not in a partisan way. This is true wherever it comes from. Left, right. Wherever. Uh, I think, you know, today, of course it's primarily coming from, from the right, but, but we as a country always need to be able to balance our concerns for security, our concerns for, uh, for ourselves. With an absolute commitment to civil liberties and wherever those are at issue, uh, regardless of whose civil liberties they are, regardless of how distant they might be from our own lives, uh, we have to recognize, uh, the possibility of continued repression and periods of oppression.

Clay Risen: And so, you know, the red scare to me then is a bright warning for anyone who wants.

Conor Kelly: Oh, did he cut off?

Clay Risen: To say thank God we've moved back. Oh, I'm sorry.

Conor Kelly: You cut off a little bit like in the middle of what you were saying, if you could repeat a little bit of what you were trying to say. No problem.

Clay Risen: Yeah, no, I think just, just to, just to reiterate that I think that people need to remember that just because the red scare happened and, and it happened for particular reasons, doesn't mean something like it can't happen again, and that we always need to be on guard to defend our civil liberties and those of other people's.

Conor Kelly: Yeah, exactly. And I think the thing that people need to remember is that they are not immune from propaganda. But I want to thank you again for joining me. This has been a wonderful interview. The book is The Red Scare, the author is Clay Risen. You can find it anywhere on your bookstores, Amazon thrift books, and a couple of other places as well, correct?

Clay Risen: Absolutely. Wherever books are sold.

Conor Kelly: Wonderful. Thanks again and have a wonderful day everybody. Thanks

If you want more content like this, please consider supporting the show!