The Model Minority Myth: A Divisive Deception

How the Model Minority Myth harms race relation

With the rise of social justice and the Black Lives Matter movement, much of the discussion surrounding racial equality and justice has been related to police brutality and violence against Black and Brown people. Despite this, the conversation surrounding subtler but no less nefarious aspects of racism in American society goes unnoticed or is actively disregarded by arguments that, while seemingly reasonable, obscure racism in this country. One such argument is the idea of the Model Minority. This perspective, while intended to show that America has overcome its racist past, is ultimately ahistorical, and serves only to downplay the challenges faced by Black Americans.

The Model Minority, as a general concept, refers to the idea that Asian Americans are evidence that America is not racist and that the challenges faced by the Black populace are not the product of systemic malfeasance, but are instead the product of some other force. Proponents of this position will argue that Asian Americans have the highest average household income in the United States, as noted by the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank. To them, this difference shows that the disparities between Black Americans and their White counterparts are not an indictment of American society’s ability to hold to its egalitarian ideals. Andrew Sullivan, a former writer for the Intelligencer, made this argument himself in 2017. But well-known supporters do not entitle an argument to legitimacy or historical accuracy. The Model Minority argument does not deal with the complexity and unique problems that face either community, and it is a blind generalization that does little to help anyone.

To preface this, it should be noted that this article is not intending to suggest that Asian Americans or immigrants didn’t have a hard and difficult life — they most certainly did — and in many cases, they still do. However, not all forms of discrimination have the same affect, nor does it mean that such discrimination was applied in the same way. Such is the case with the Model Minority myth. For one, the Model Minority myth has a direct correlation to White efforts to denigrate Black Americans. In his 1996 essay, sociologist William Pettersen, who helped popularize the Model Minority stereotype, made comparisons between Black and Asian populaces, comparing the abuse that Asians and Black Americans faced and went so far as to argue that the reason for Asian American success was an example of good character and work ethic, in addition to improvements in education. His thesis, ultimately would ultimately serve as the framework for the modern Model Minority myth.

An improvement in education did play some role, but, as Nathaniel Hilger, an economist at Brown University, notes Asian Americans began to see an improvement not due to their educational attainment, but due to improved opportunities that were created by a decreased hostility towards the Asian populace. Asian Americans began to receive equal and sometimes greater payment than their White counterparts across education levels. Asian Americans saw an improvement, because, like other groups before them, powerful people needed them to improve to maintain their power.

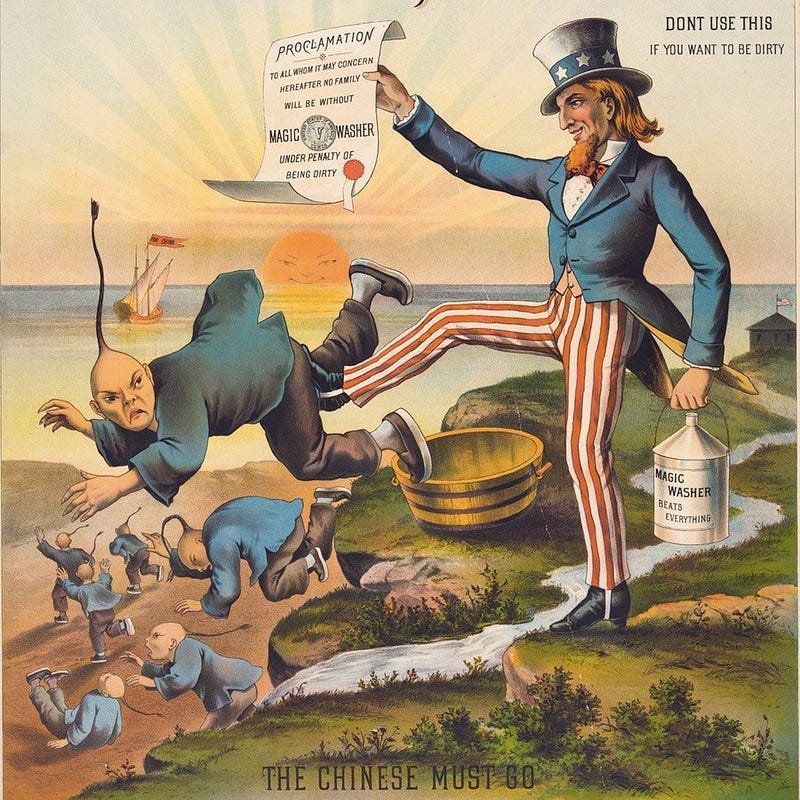

From the beginning, Asian Americans have contributed significantly to the American enterprise. The first wave of Asian Americans came from China in the 1800s, with many of these migrants coming to work the railroads in California. The Chinese Massacre of 1871, however, showed that Asian Americans were not welcome in the United States despite their work ethic. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed, prohibiting the entry of Chinese immigrants into the United States. It was one of the first pieces of legislation that explicitly prohibited immigrants from coming to the United States on the basis of their nationality. This act, passed by then-President Chester A. Arthur, was largely seen as Chester’s way of throwing a bone to xenophobic Americans in a bid for votes. Indeed, it would end up creating strict racial quotas for immigration.

When the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943, it was not because of altruistic intentions by the American masses. The Magnuson Act of 1943, which repealed the Exclusion Act, was in response to The Citizens Committee to Repeal Chinese Exclusion, who saw the ban on immigration as a threat to America’s alliance with China against Japan, as noted by historian and author, Ellen D. Wu. This threat, however, did not stop the Magnuson Act from putting a strict quota of only 150 Chinese immigrants per year, restricting the Chinese immigrants to those seen as most useful to American society. With the fall of Imperial Japan after World War 2, fear of Asian Americans began to decline, and other groups, such as Koreans, and Filipinos began to see an improvement in their rights, with many gaining citizenship. It was no longer useful to denounce Asians and to hold those who held connections to Asia with such disdain, at least not as much as it had once been. Many of the aforementioned groups, including Japanese Americans, also touted their service to America in the war as a sign of their discipline and value. Though fears of Asians would decline, it would take decades before the benefits of their service would be truly felt.

By the 1950s, Asian Americans, and in particular Chinese Americans, were once again used as the ideal for integration, with newspapers such as the U.S. News and World Report promoting their “obedience” to their elders and traditional values that fit well with the conservative narratives of the time. Where they were once seen as the worst society had to offer, Asian Americans, again Chinese in particular, were seen as the ideal to be upheld, especially in the 60s. In the 1960s, this would become the narrative in response to the Civil Rights and Black Freedom Movements, seeking to undermine their grievances. This was not without its harms for Chinese Americans and Asian Americans alike, who, as political scientist Ling-Chi Wang noted, would be neglected by the American government so long as they were held to inhuman, mythologized standards. As writer Frank Chin said of the imposed mythology, “Whites love us because we aren’t Black.” If White America wasn’t going to be altruistic in the 1940s, it wasn’t going to be altruistic in the 1970s either; they were being strategic.

This mythologized and selective approach to understanding of Asian Americans would be spread across the board, with little room for nuance or historical context, and irrespective of the agency of Asian Americans in their own story. Despite what proponents of this myth may claim, the Asian American experience is not the Black experience, nor will it ever be. For one, Asian American history is largely one of migration and integration, whereas Black history is the product of forced enslavement and kidnapping. We can see the effects of this difference very clearly in migration patterns. According to the Pew Research Center, 78 percent of Asian American adults are immigrants or foreign born as of 2016, compared to just 9 percent of Black Americans. This draws a clear distinction in circumstance, as Black Americans are subject to many domestic problems that are directly connected to systemic racism from a young age in ways that aren’t as likely be enforced on the Asian American populace.

To reiterate, Asian Americans have faced a significant hardship and violence against Asian Americans has skyrocketed thanks to the pandemic. But that does not change that such challenges are far different from the challenges faced by the Black community.

The Immigration Act of 1990 has contributed partially to this rise in educational attainment, with a rise in high-skill jobs coming not long after the act was passed, many of whom were immigrants. In essence, the rise of Asian Americans is the rise of the immigrant, something that plays far less of a role in the Black community.

If we are to truly understand the complexities of racism, then we must first recognize the fact that the experiences of differing groups vary wildly, creating a plethora of results. By recognizing those results, we can see the role of race in American society so that we may change America into a more egalitarian and free nation — a nation that works through unity, not mythologized derision that serves only to disregard Black voices.

Originally published in the Lorian at Loras College and republished in An Injustice!

A new intersectional publication, geared towards voices, values, and identities!medium.com